Joel Janowitz | Refuge

Joel Janowtiz’s new paintings and monotypes create a Refuge for the viewer, a safe space where one can feel protected and secure. Refuge for Janowitz has become the greenhouses at Wellesley College. First painted in the 1970s, he returns to the subject with a new series. The brush strokes are freer, the content more abstract, and his extraordinary use of light and dark illustrate day and night. Painted during a long period of isolation, the resulting pieces are not about loneliness but a meditative solitude and hope.

This exhibition presents my fourth series of greenhouse paintings. In the mid 1970s, I worked from life at the Ferguson Greenhouses at Wellesley College. That first series focused on the complex structure of light and space within the greenhouse, resulting in work that felt lively yet quietly contemplative. In the 1980s, I returned to the greenhouse theme, this time at night, to paint the contradictions and mystery of artificial illumination and darkness in its normally sun-filled interior. A third series from the early 2000s dissolved and abstracted the spatial structure, with loosened brushwork and invented color.

Now, 2021 has brought me back to greenhouse imagery again. As we live through the isolation of the pandemic and the growing anxiety of global warming, these paintings suggest a refuge of safety

without ignoring the cacophony and weight

of our current crises. J. Janowitz, 2021.

Janowitz, a Boston-based artist, has exhibited his works since 1973, both in the United States and abroad – totaling 30 solo exhibitions to date. His work is in numerous collections, including Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; University of California, Santa Barbara, CA; The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA; and the Fogg Museum at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. The recipient of many awards, Janowitz received two grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, a 2008 & 2016 Artist Fellowship in Painting from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, and a 2013 Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.

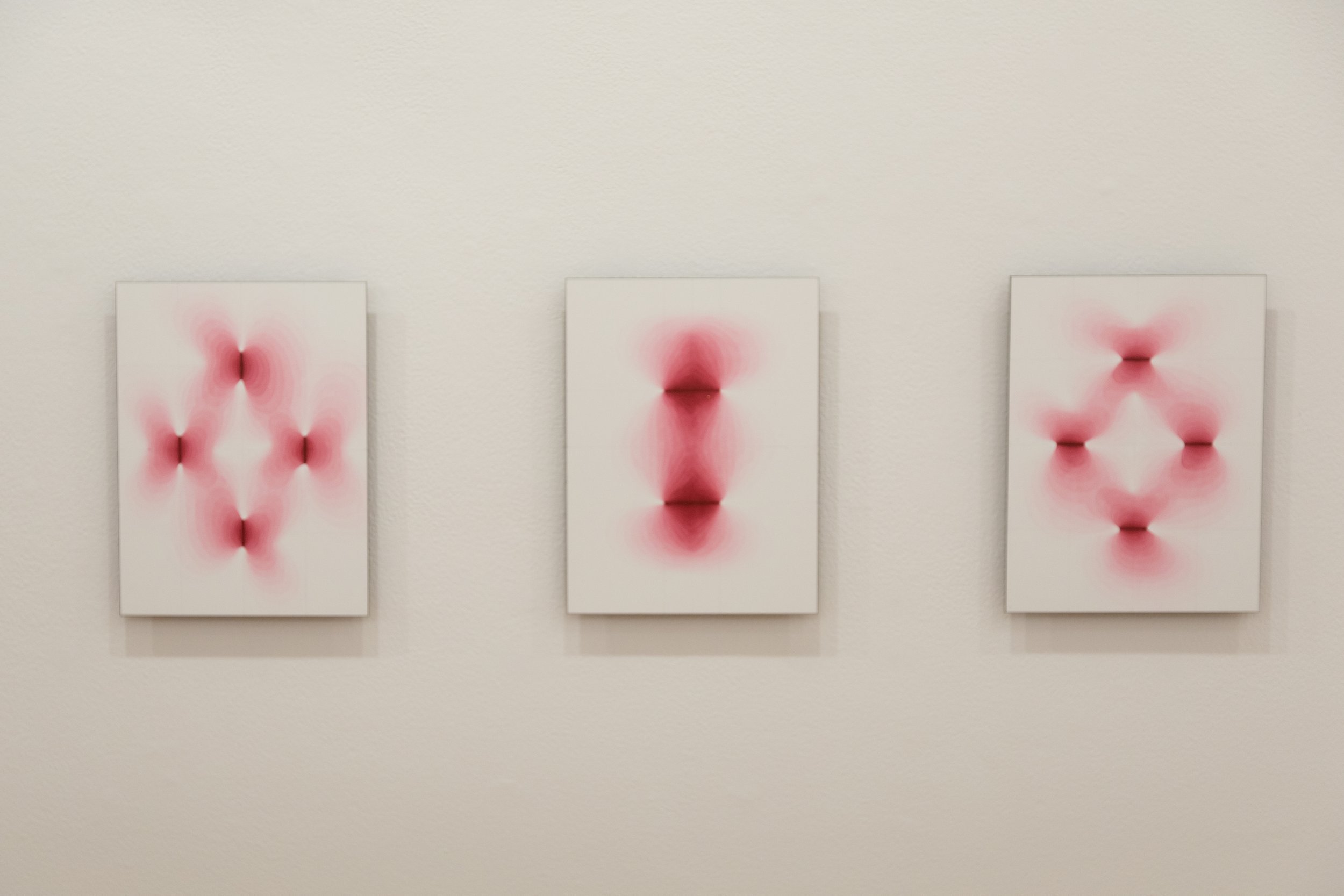

Anne Lilly | Events in a Field

Anne Lilly’s events in a field is a series of 18 new paintings using both watercolor and acrylic. Painted on panels and without the confinement of the frame, they become sculptural objects. The vibrating lines and patterns of Lilly’s mark-making are hypnotic––coupled with her use of color, this movement creates a three-dimensional quality that alters our perceptions.

e v e n t s i n a f i e l d Over the past year, it struck me that my way of painting has a metaphor in farming, a posthumous bequest from my grandparents perhaps. After drawing a grid on a flat surface, I insert an array of marks into it, then cover the marks with a succession of enlarging and ever-paler washes. They thereby grow in organic and unpredictable ways, retaining the traces of earlier states. The whole field becomes an intricate and incremental record of time’s progress. The paintings that result from this cultivation feel to me like accurate representations of what it means to be alive in the world: events in the subtle continuum constituting everything that exists. By contrast, our every day and pragmatic state of mind posits reality as an infinite population of sharply distinguished, durable things. You are separate from me. This plant is distinct from that animal. The earth is clearly delineated from the sky. But if you imagine watching any of these for a hundred years or so, they change. Take a handful of dirt, for instance. Over a century, it can change into many things. In my own imagination, it changes into Oklahoma. My mother in her childhood, her parents for much of their lives, and all of their kin around and before them, farmed the drought-ridden prairie of southwest Oklahoma. They were sharecroppers, too poor to own the land they worked, instead paying a fee to the landlord. They raised cotton, or tried to, until the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, and the locust swarms set in. After the 1889 Land Rush, three generations of farming had stripped that magnificent landscape of its buffalo, its virgin prairie tallgrass (“high as the chest of a man on horseback,” according to family lore), and its fertile topsoil. By the 1940s, the farmers had thoroughly impoverished the land, and the land impoverished them in return. My mother and all her family are buried there now, surrendered and assimilating with the clay, which brings us back to my thought-experiment. For me, that clod of earth in my hand blurs into a withered cotton boll and my mother’s blighted life. Further back, both the cotton and my mother lapse into the parched, furrowed fields from which they arose. Back further still, and the earth’s richness is restored with the buffalo that graze and blend with their towering forests of grass. In this vista of intimate and incremental succession, nothing is separate. Each thing flows into the next. The edges are fuzzy at best. anne lilly DECEMBER 2021

Lilly holds a Bachelor of Architecture, graduating magna cum laude from Virginia Tech, and has taught at MIT and Massachusetts College of Art. She received the Barnett and Annalee Newman Foundation Grant Award for Lifetime Achievement, the Blanche E. Colman Grant, visiting artist positions at the Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the Art Institute of Boston. Lilly’s work was included in a landmark 14-month exhibition of kinetic art at the MIT Museum. The deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum has collected her work along with the New Britain Museum of American Art, the Middlebury College Museum of Art, and numerous corporate and private collections internationally. In March 2017, she was an invitational lecturer and guest critic at Lebanese American University, in Beirut, Lebanon.

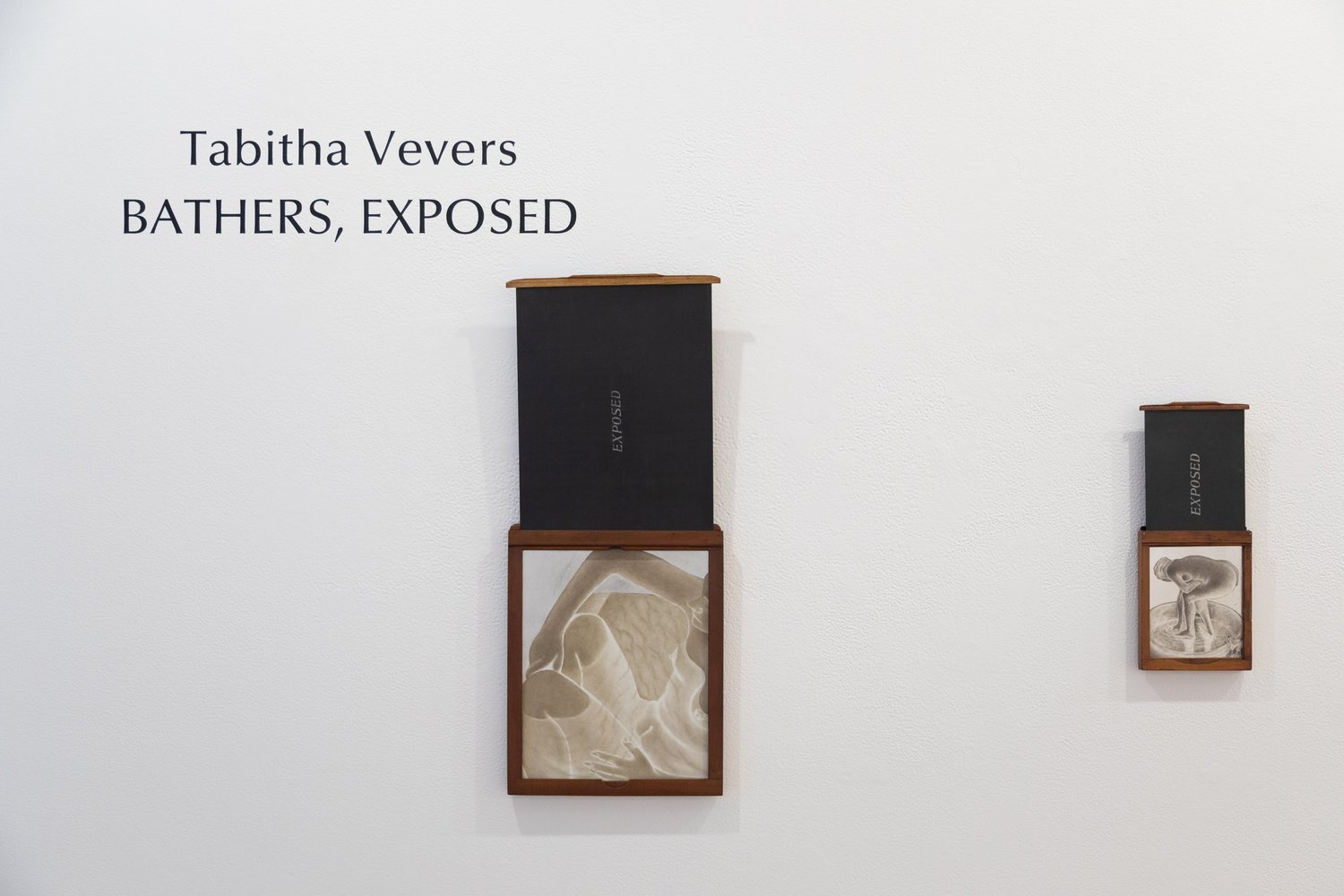

Tabitha Vevers | Bathers, Exposed

We are excited to be exhibiting Tabitha Vevers’ new series, BATHERS, EXPOSED as we welcome her to the Gallery. Her 18 powerful paintings on vintage wooden film holders are of bathers appropriated from art history. The referenced paintings have been reversed from positive to negative, completely changing the nature of each painting and its colors. They are small and fit discretely into the film holders, which measure up to 8x10”. When the holder is closed, “EXPOSED” is evident. When the slide is raised, the painting is visible. They are delicate, intimate, and specific to the original painting – with the reveal, we become the voyeur.

A nude photograph of Lee Miller in a bathtub was the catalyst for this work. Taken in 1930 by her father, Theodore Miller, it seemed to exemplify the inescapability of the male gaze. We often speak of “taking” or “capturing” an image, implying possession, which is particularly loaded when speaking of nudes. In Bathers, Exposed, I’ve painted bathers appropriated from art history, framing them to be physically contained within vintage wooden film holders, much as photographic negatives would be.

The structure of the film holders—mechanically complex and yet ingeniously simple—became integral to the work. Their thin black slides, often imprinted with the word “EXPOSED,” can be raised or lowered, concealing or exposing the bathers to varying degrees. With this peep show effect, the flesh of the bathers becomes analogous to the film the holders were designed to protect and, the viewer is transformed into voyeur.

Inverting the images from the positive to the negative in black and white or converting color images into their “opposite” or complementary colors seemed logical. In doing so, I was struck by how flesh tones became various shades of blue, reminiscent of Matisse’s Blue Bathers. Perhaps Matisse’s inspiration came from closing his eyes after intense study of his models, seeing them etched on his eyelids in the opposite of warm flesh tones—complementary blue. I considered mounting the paintings upside-down in the film holders, as they would be seen on the ground glass of a view camera, but ultimately decided against it. In a final nod to photography, I have incorporated palladium leaf into most of the paintings, referencing early palladium prints.Tabitha Vevers 2021

(In 2018, Gus and Arlette Kayafas loaned me a gelatin silver print of “Lee Miller in the Bath” by Theodore Miller, after seeing a number of paintings, sculptures and a short film I had done exploring the relationship between Lee Miller and Man Ray.)

Tabitha Vevers is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including grants from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, The George + Helen Segal Foundation, and the Massachusetts Artists Foundation, and painting fellowships to The Ballinglen Arts Foundation (Ireland), Oberpfälzer Künstlerhaus (Germany), Fine Arts Work Center, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and The MacDowell Colony. Vevers was a co-founder of artSTRAND and has served as a member of the curatorial committee of the Provincetown Art Association + Museum, the admissions panel of the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and the Artists’ Advisory Board of Castle Hill Center for the Arts. She received her B.A. from Yale University and studied at Skowhegan School of Painting + Sculpture.

Vevers has exhibited across the country and Europe, having work in numerous public and private collections. Her work is currently on exhibit in On the Basis of Art: 150 Years of Women as Yale, at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT. It was the subject of a comprehensive exhibition, Tabitha Vevers: Lover’s Eyes, at The Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, SC in 2019-20 and was featured in a major exhibition entitled GOLD, at the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, Austria in 2012. She was honored with a mid-career retrospective entitled Narrative Bodies at the deCordova Sculpture Park + Museum in 2009.