August Sander

Just Women

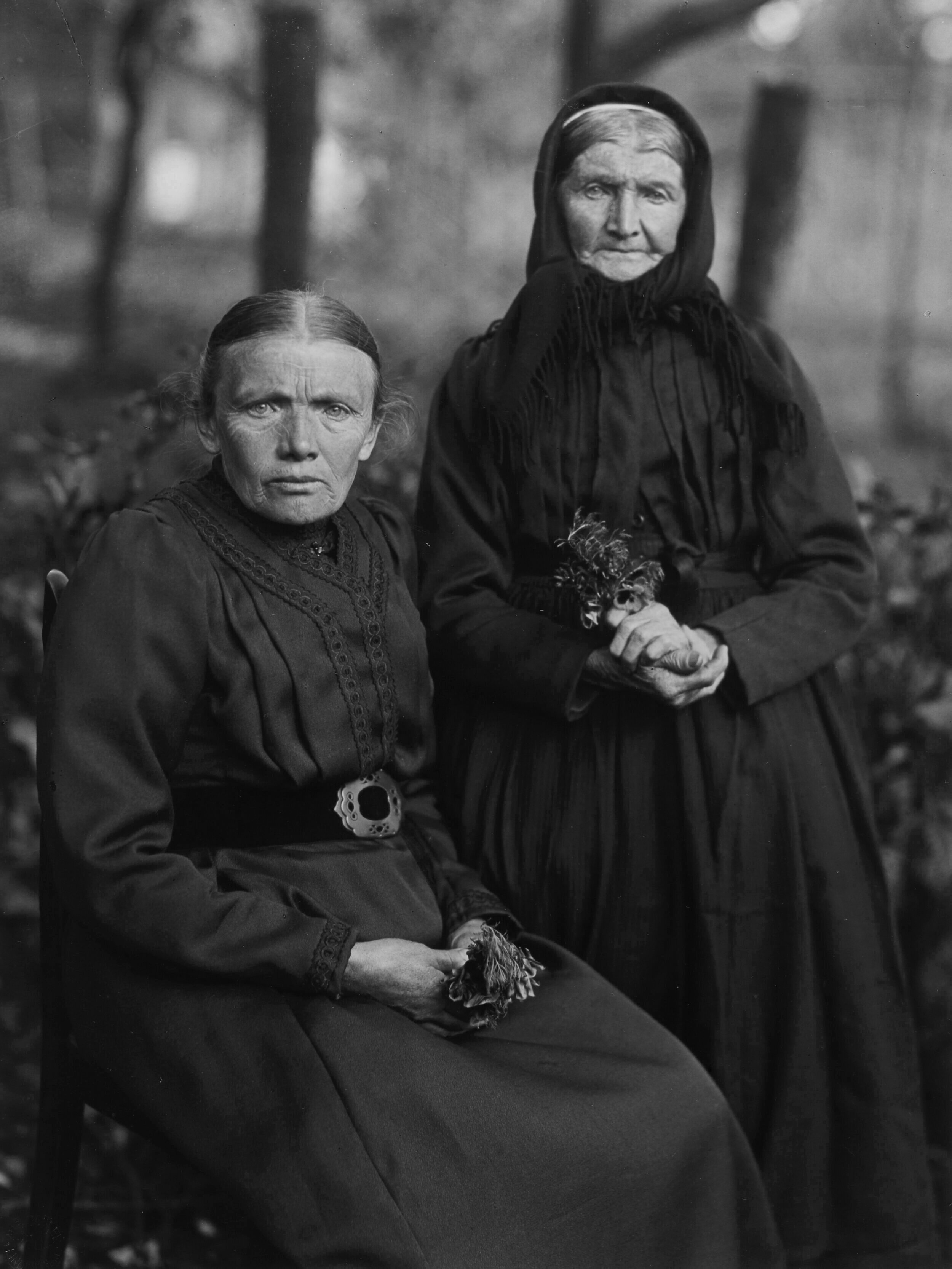

August Sander (1876-1964), based in Cologne, Germany, photographed landscapes, nature, architecture, and commercial subjects, but he is best known for his portraits and is often described as “the most important German portrait photographer of the early twentieth century.” He was part of a very active and cultured society, many of his friends were significant artists, all were deeply affected by the rise of the Nazi regime.

Beginning in 1911, Sander began a series of portraits comprising his master project, People of the 20th Century. In addition to his very successful commercial practice, guided by his plan, he spent weekends traveling by bicycle to farm communities, country fairs, and other events that gave him access to subjects less likely to hire him. He made unique portfolios based on categories that grouped his subjects: The Farmer, The Skilled Tradesman, Woman, Classes and Professions, The Artists, The City, and, The Last People. Nearly 700 images representing decades of obsessive work were finally edited and presented. For this exhibit, I have chosen only images of women, selecting from each of the seven volumes enabling me to show many different social and economic backgrounds.

This group of portraits presents a diversity in a wide range of roles women fulfilled in the early 20th century as indicated in Sander’s titles: The Woman of Soil, 1912; The Woman of Progressive Intellect, 1914; Politician, 1929; Widow with her Sons, 1921; Real Estate Agent, 1928; and Painter’s Wife (Helen Abelene), 1926. These are a few of the 23 separate identities in Just Women. People of the 20th Century is Sander’s brilliant obsession, his observations of the German people and society.

Jess T. Dugan

Every Breath We Drew

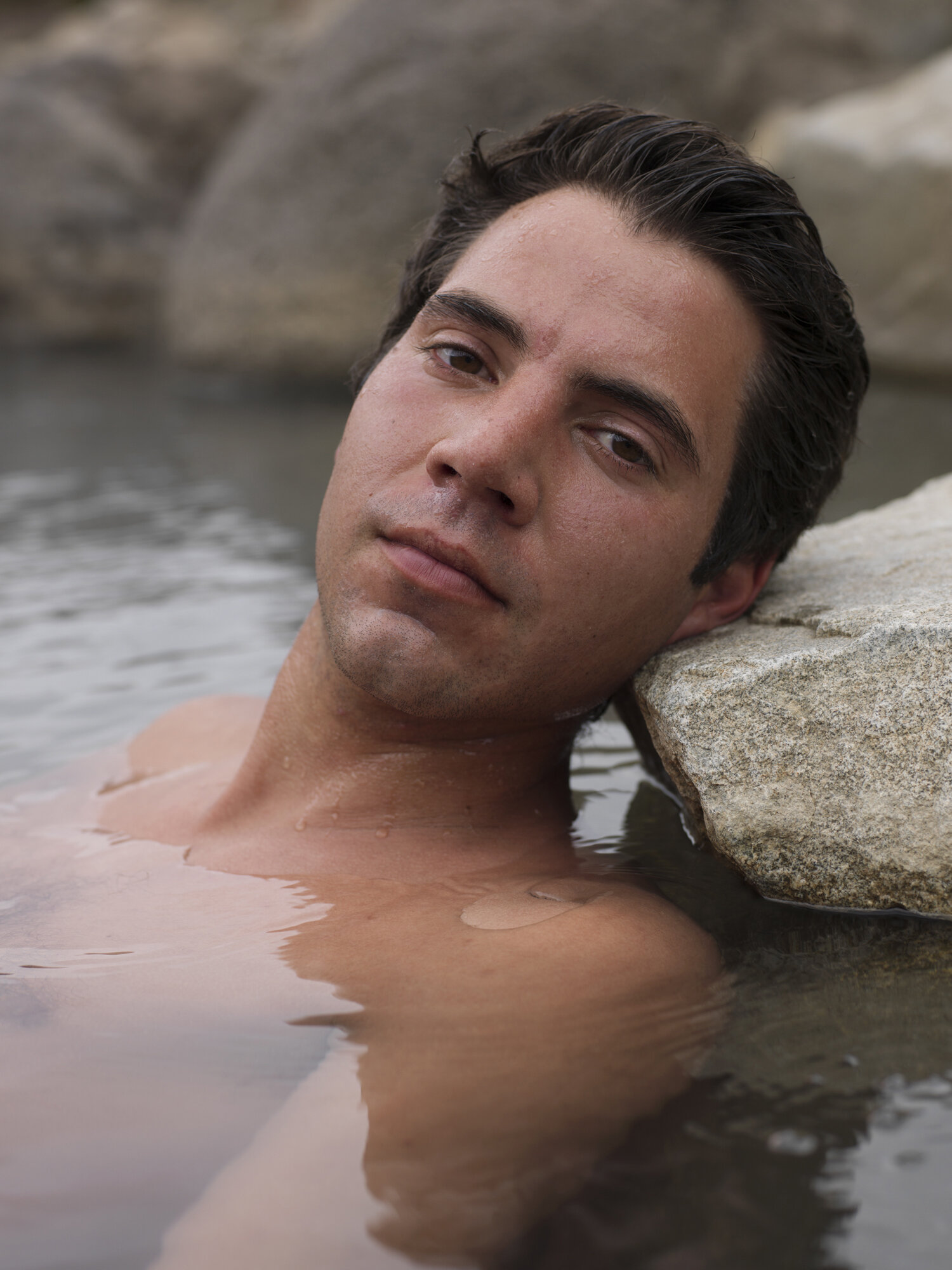

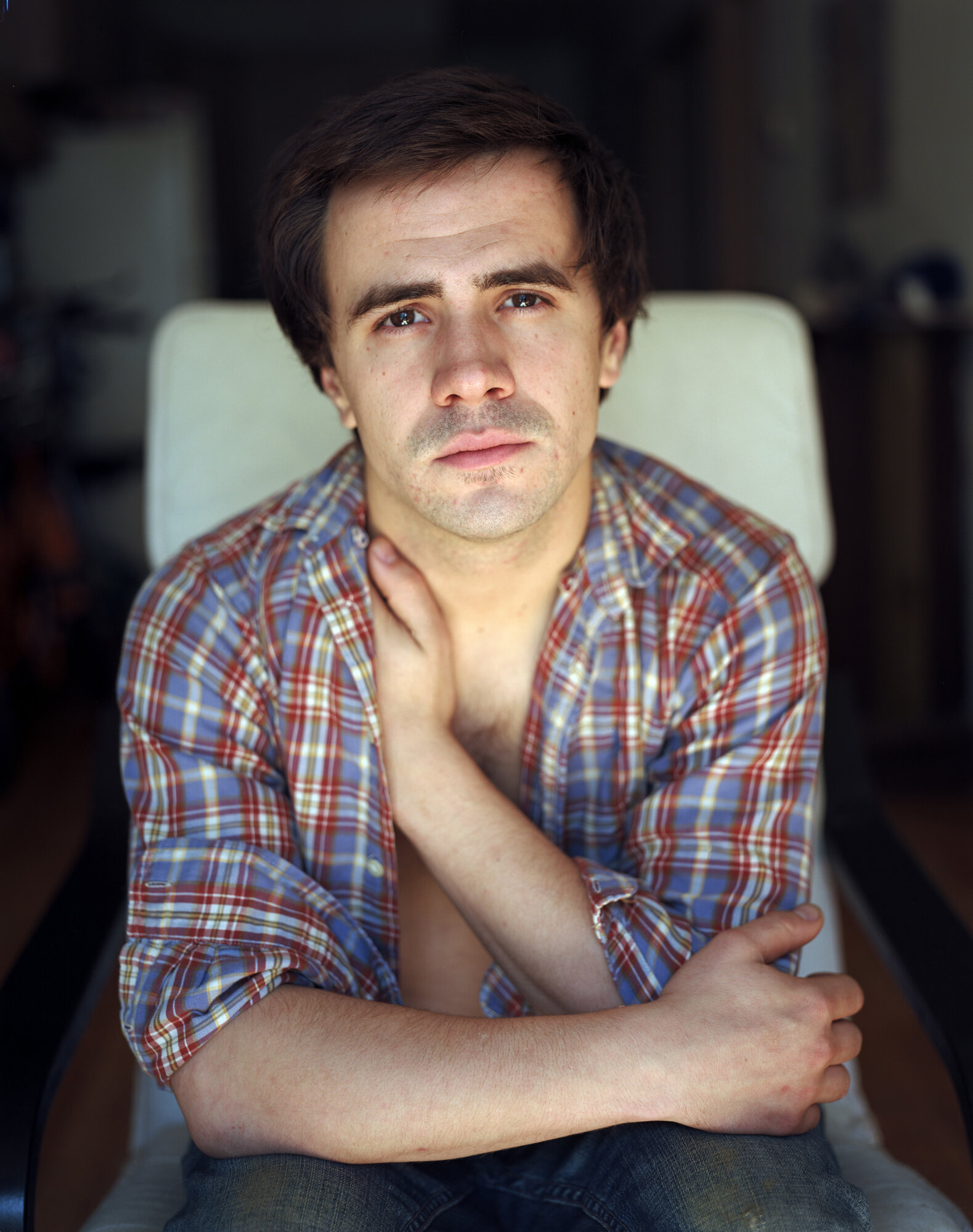

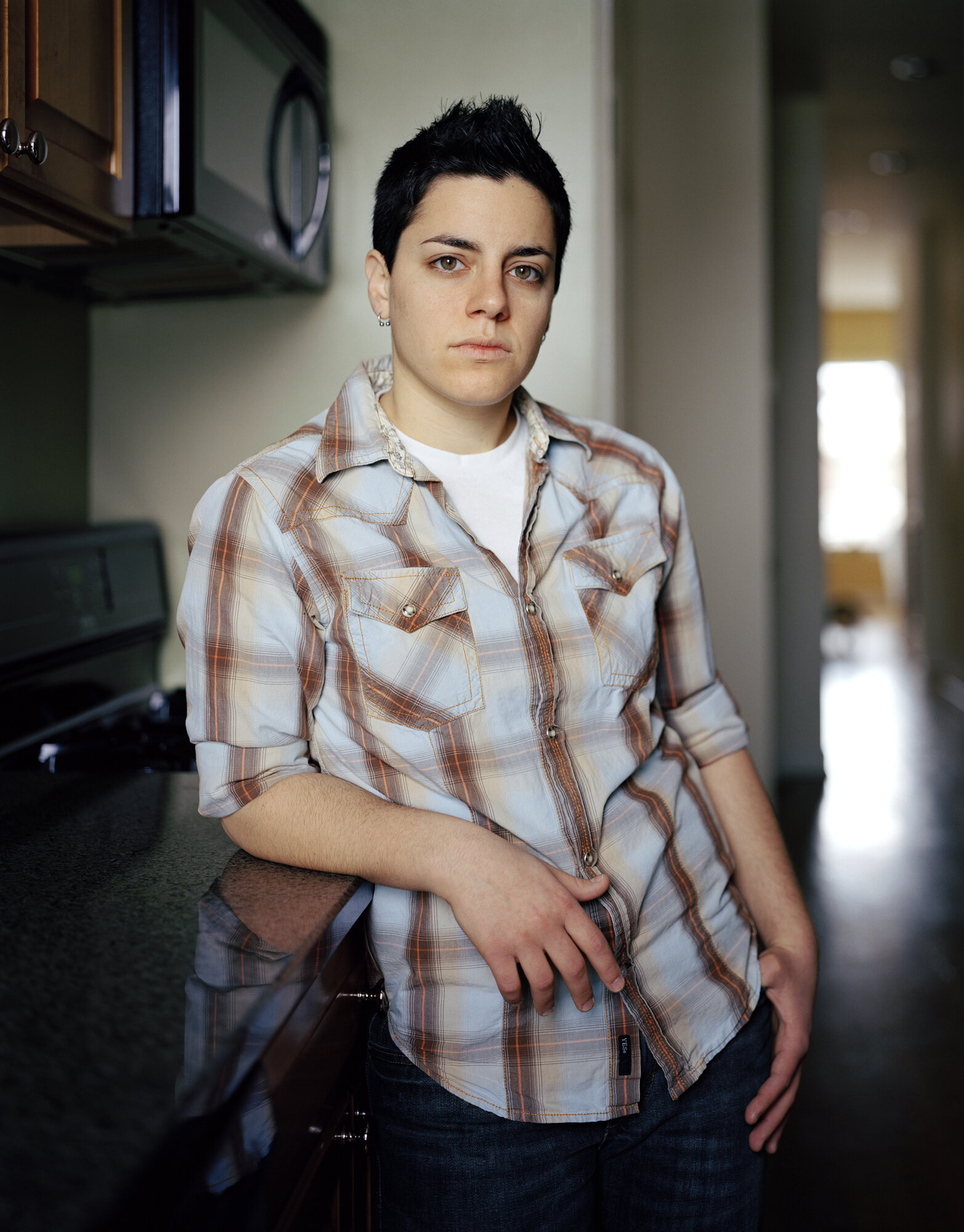

Every Breath We Drew represents the continued exploration of identity through the queer experience. As Sander’s People of the 20th Century, asks the viewer to question identity through social structure and employment, Every Breath We Drew asks us to take identity to the next level and to consider the connections between one’s private identity and the multiplicity of today’s gender definitions — no longer just two genders but a society of endless variations.

Dugan’s color self portraits and others reveal an intimacy and trust developed with the subjects — Jess does not separate self from this process but rather becomes an active part of the exploration invoking a personal understanding and commitment. Unlike Sander’s descriptions, Dugan identifies the individual by name — names deeply influence how gender is perceived. Dugan is asking us to do more than look, but to see. We encounter these portraits and examine how visual clues can define, even limit, perception. Does our perception affect the observed reality? Can we see the individual without identifying gender? Can we take this visual experience and see beyond what limits us?

Both Sander and Dugan present us with their observed reality. While their experiences are separated by almost a century, each artist’s commitment to their portraits reveals the shared experience of being human. We have the opportunity through committed visual encounter to broaden our perception and understanding.