Anne Lilly: events in a field

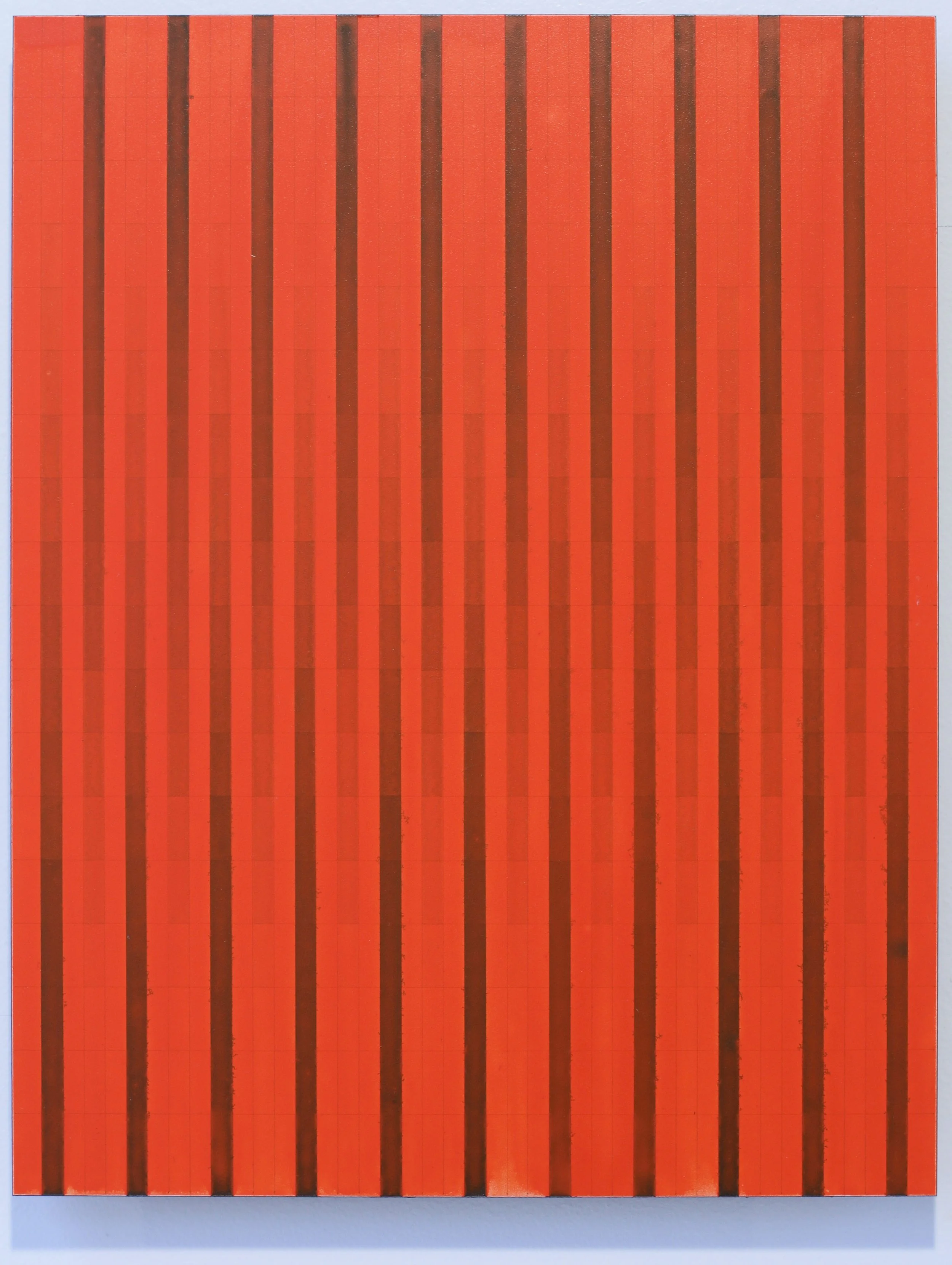

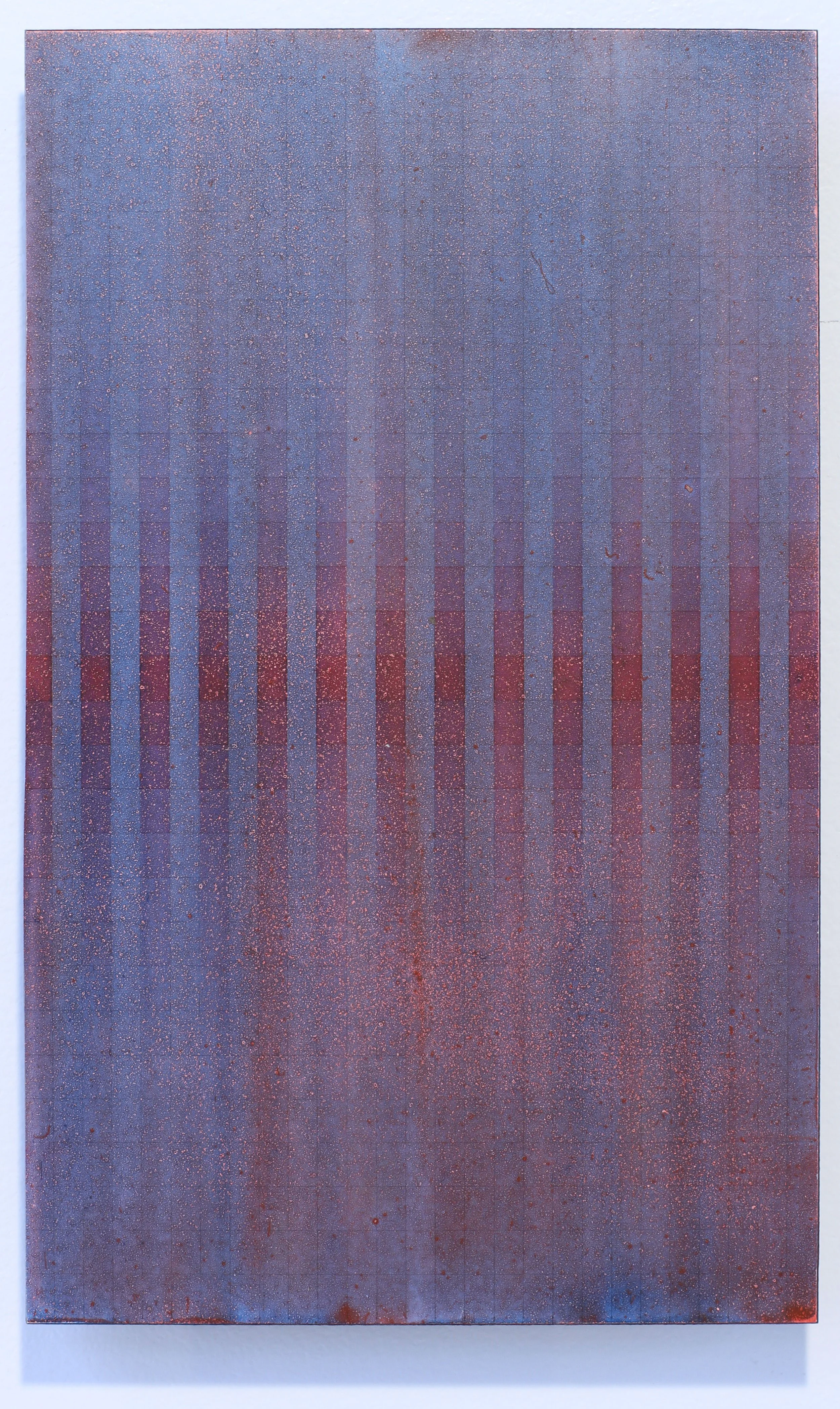

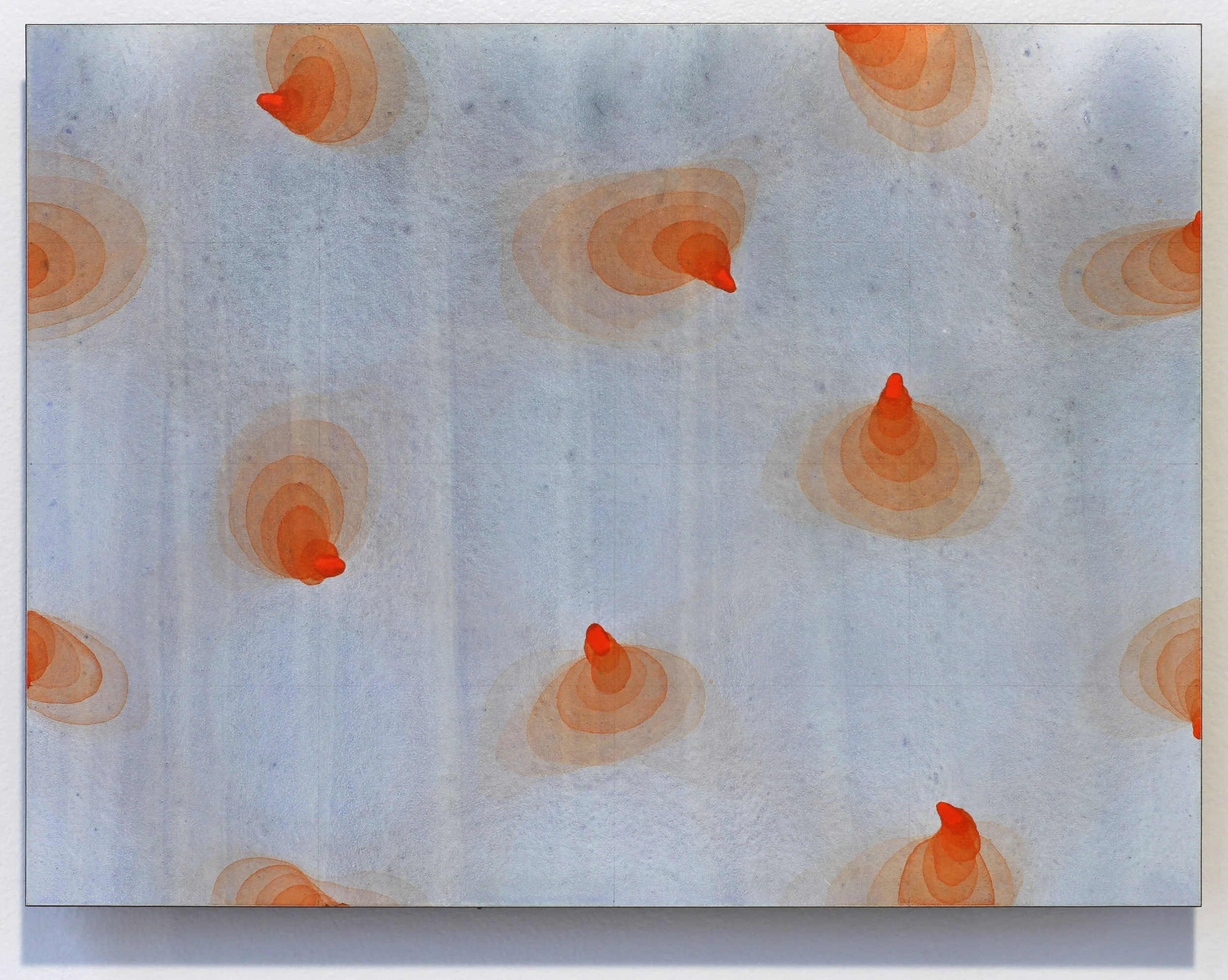

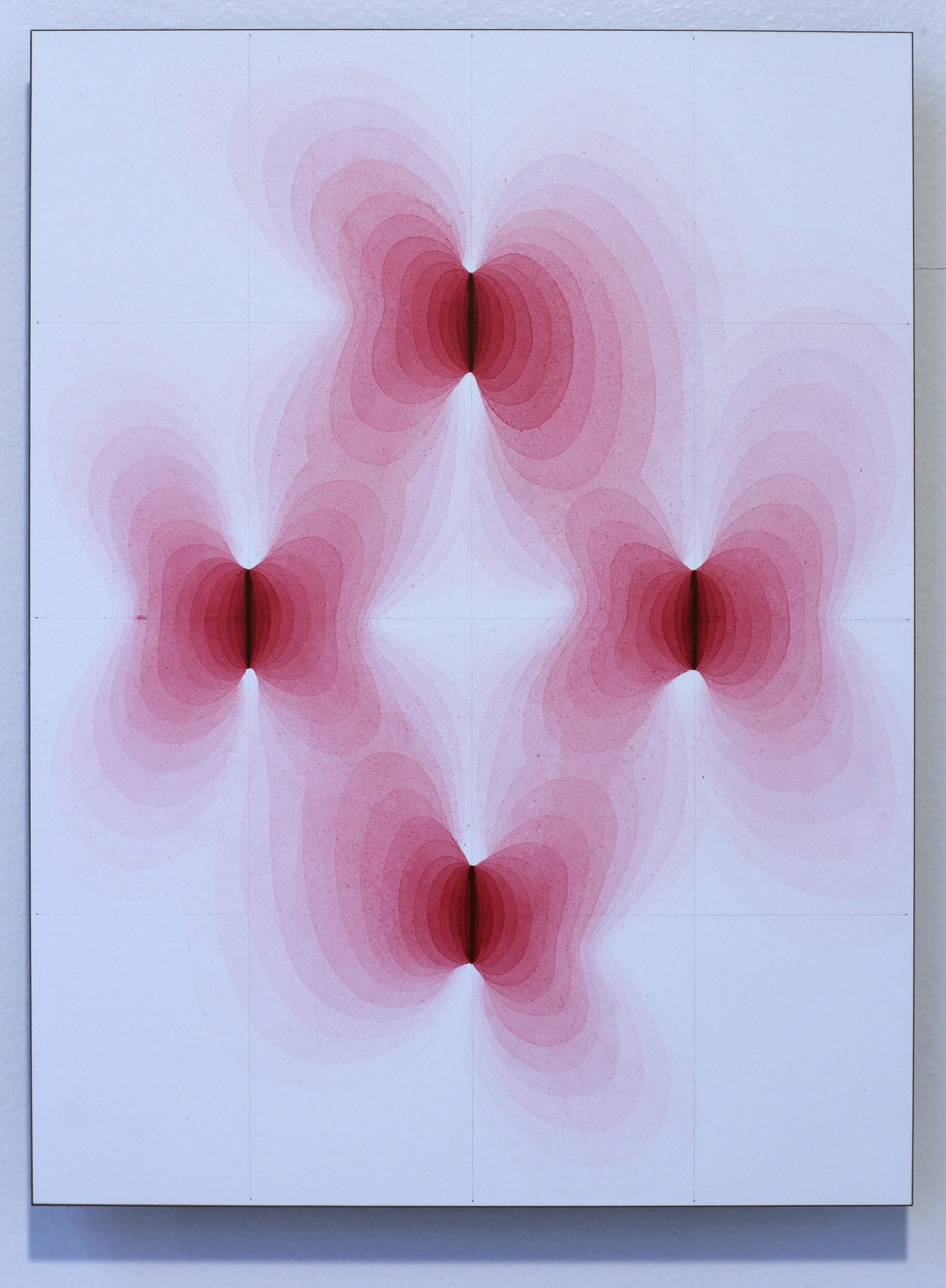

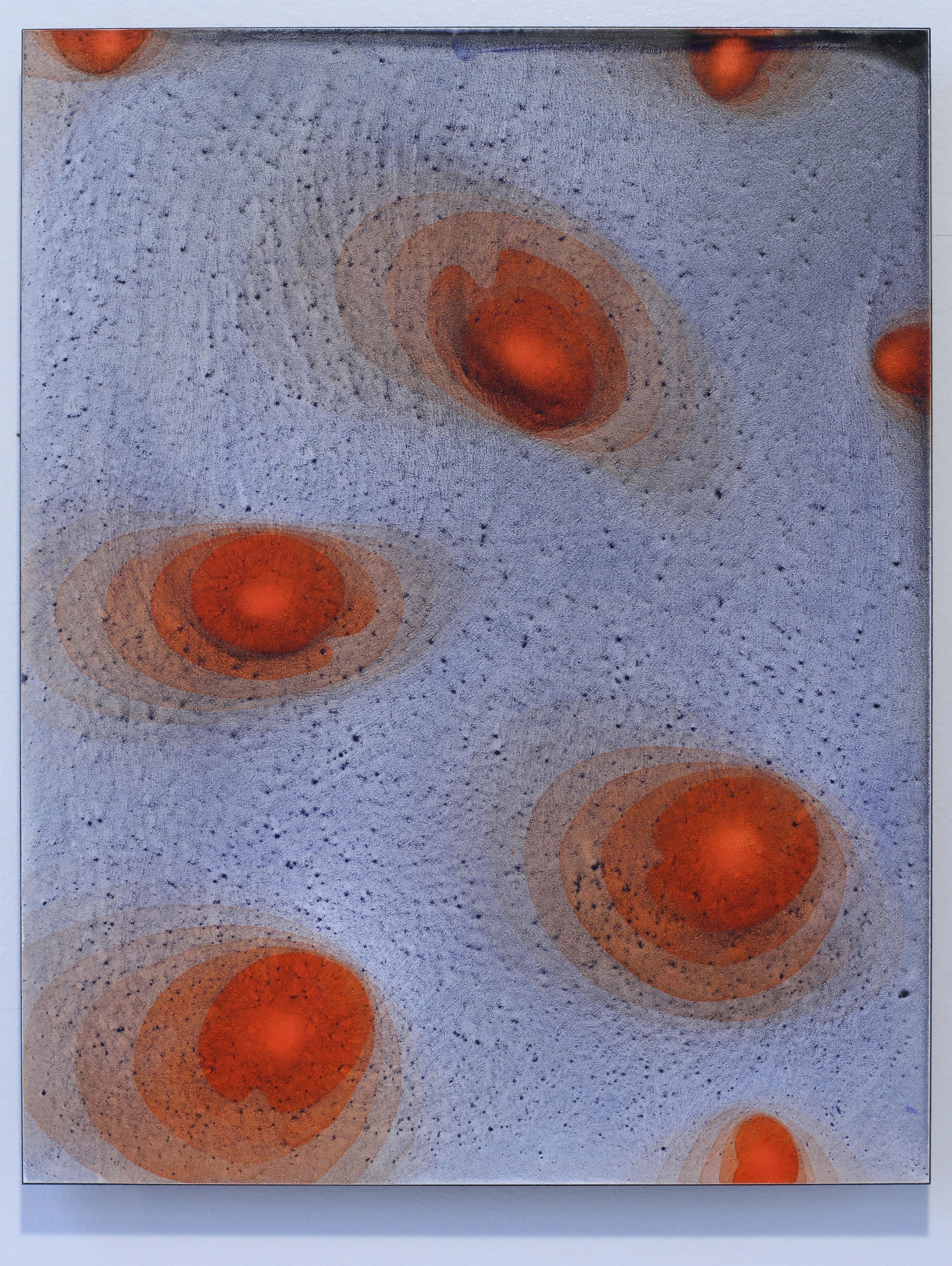

Anne Lilly’s events in a field is a series of 18 new paintings using both watercolor and acrylic. Painted on panels and without the confinement of the frame, they become sculptural objects. The vibrating lines and patterns of Lilly’s mark-making are hypnotic––coupled with her use of color, this movement creates a three-dimensional quality that alters our perceptions.

e v e n t s i n a f i e l d Over the past year, it struck me that my way of painting has a metaphor in farming, a posthumous bequest from my grandparents perhaps. After drawing a grid on a flat surface, I insert an array of marks into it, then cover the marks with a succession of enlarging and ever-paler washes. They thereby grow in organic and unpredictable ways, retaining the traces of earlier states. The whole field becomes an intricate and incremental record of time’s progress. The paintings that result from this cultivation feel to me like accurate representations of what it means to be alive in the world: events in the subtle continuum constituting everything that exists. By contrast, our every day and pragmatic state of mind posits reality as an infinite population of sharply distinguished, durable things. You are separate from me. This plant is distinct from that animal. The earth is clearly delineated from the sky. But if you imagine watching any of these for a hundred years or so, they change. Take a handful of dirt, for instance. Over a century, it can change into many things. In my own imagination, it changes into Oklahoma. My mother in her childhood, her parents for much of their lives, and all of their kin around and before them, farmed the drought-ridden prairie of southwest Oklahoma. They were sharecroppers, too poor to own the land they worked, instead paying a fee to the landlord. They raised cotton, or tried to, until the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl, and the locust swarms set in. After the 1889 Land Rush, three generations of farming had stripped that magnificent landscape of its buffalo, its virgin prairie tallgrass (“high as the chest of a man on horseback,” according to family lore), and its fertile topsoil. By the 1940s, the farmers had thoroughly impoverished the land, and the land impoverished them in return. My mother and all her family are buried there now, surrendered and assimilating with the clay, which brings us back to my thought-experiment. For me, that clod of earth in my hand blurs into a withered cotton boll and my mother’s blighted life. Further back, both the cotton and my mother lapse into the parched, furrowed fields from which they arose. Back further still, and the earth’s richness is restored with the buffalo that graze and blend with their towering forests of grass. In this vista of intimate and incremental succession, nothing is separate. Each thing flows into the next. The edges are fuzzy at best. anne lilly DECEMBER 2021

Lilly holds a Bachelor of Architecture, graduating magna cum laude from Virginia Tech, and has taught at MIT and Massachusetts College of Art. She received the Barnett and Annalee Newman Foundation Grant Award for Lifetime Achievement, the Blanche E. Colman Grant, visiting artist positions at the Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the Art Institute of Boston. Lilly’s work was included in a landmark 14-month exhibition of kinetic art at the MIT Museum. The deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum has collected her work along with the New Britain Museum of American Art, the Middlebury College Museum of Art, and numerous corporate and private collections internationally. In March 2017, she was an invitational lecturer and guest critic at Lebanese American University, in Beirut, Lebanon.

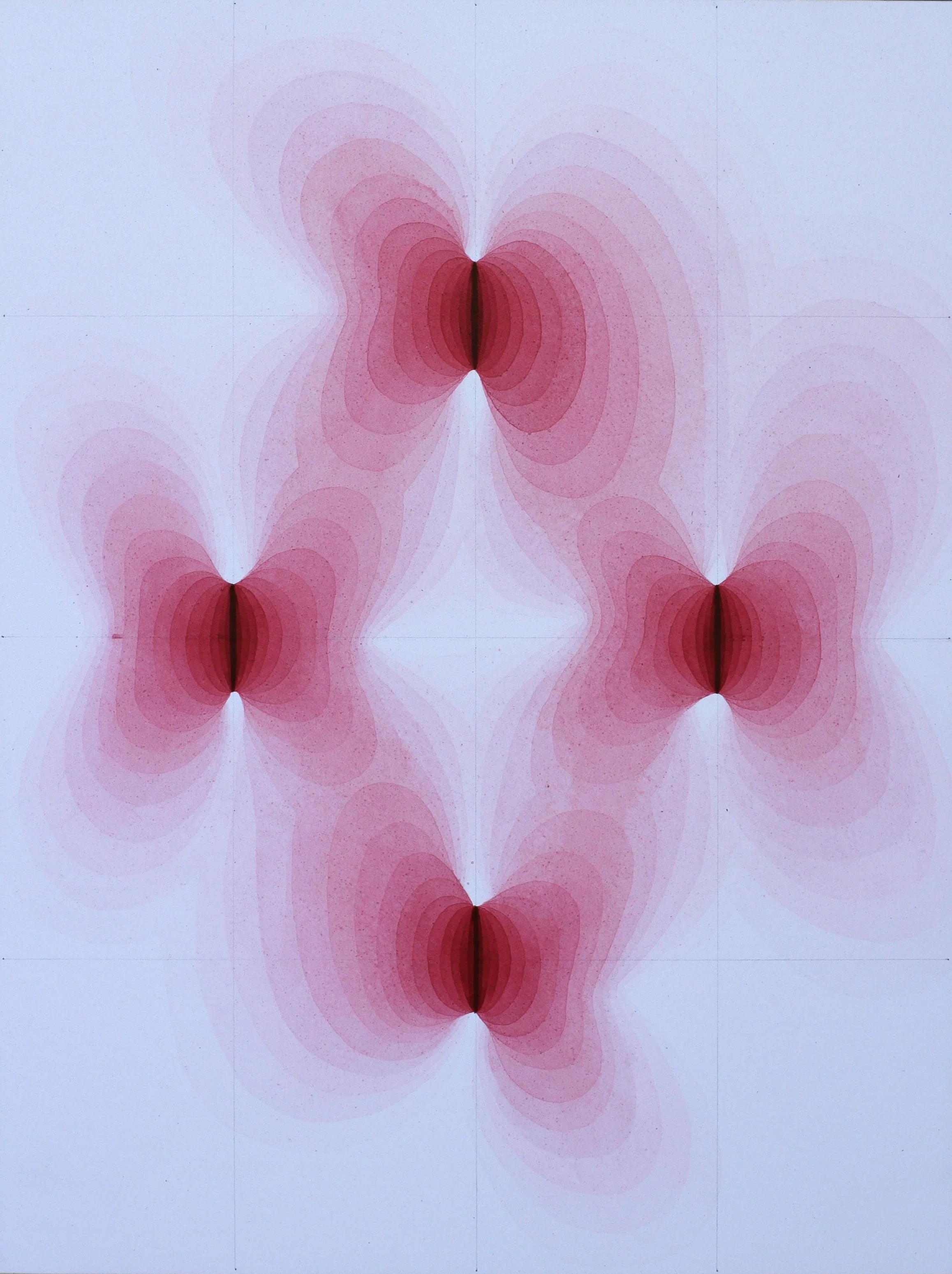

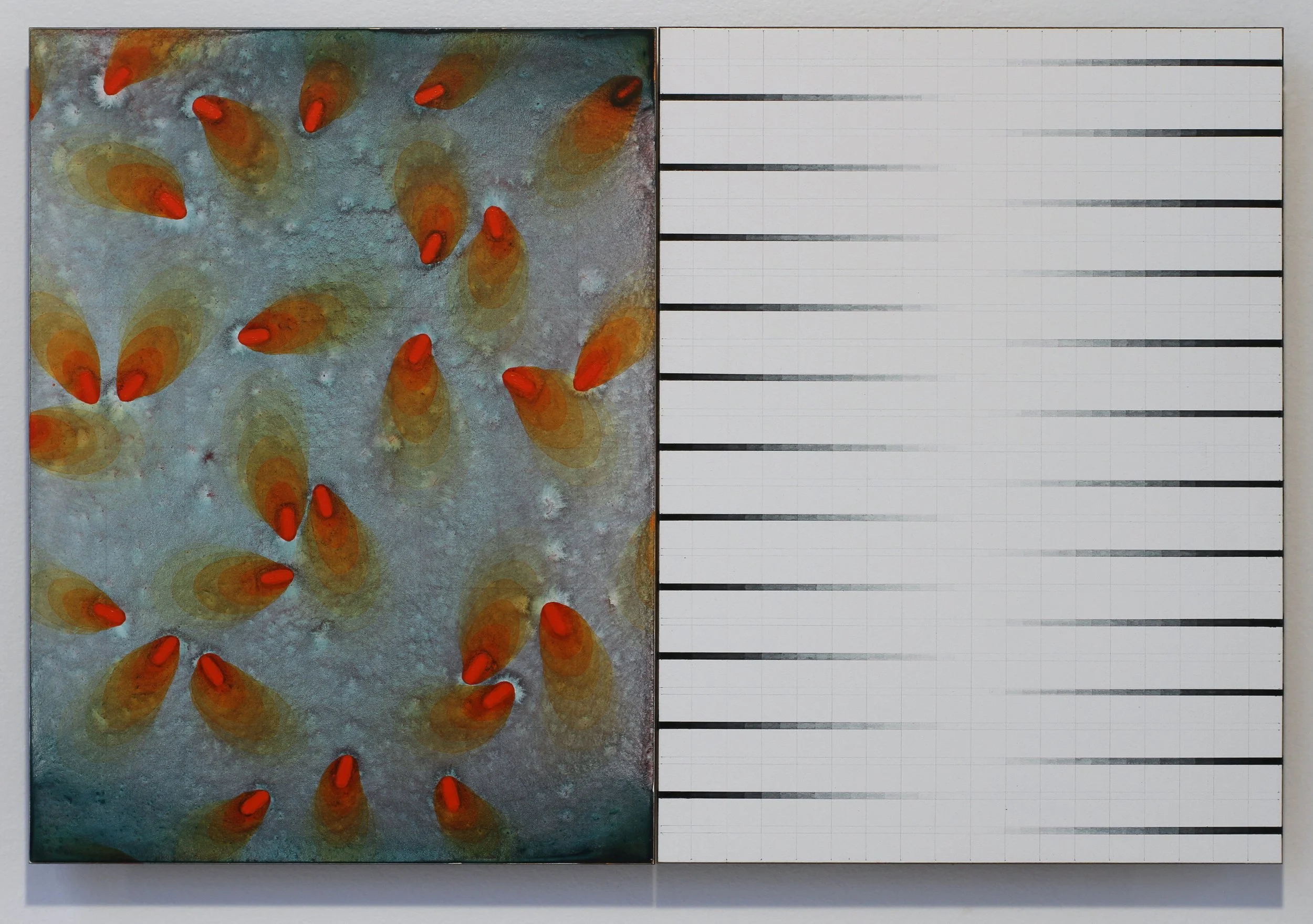

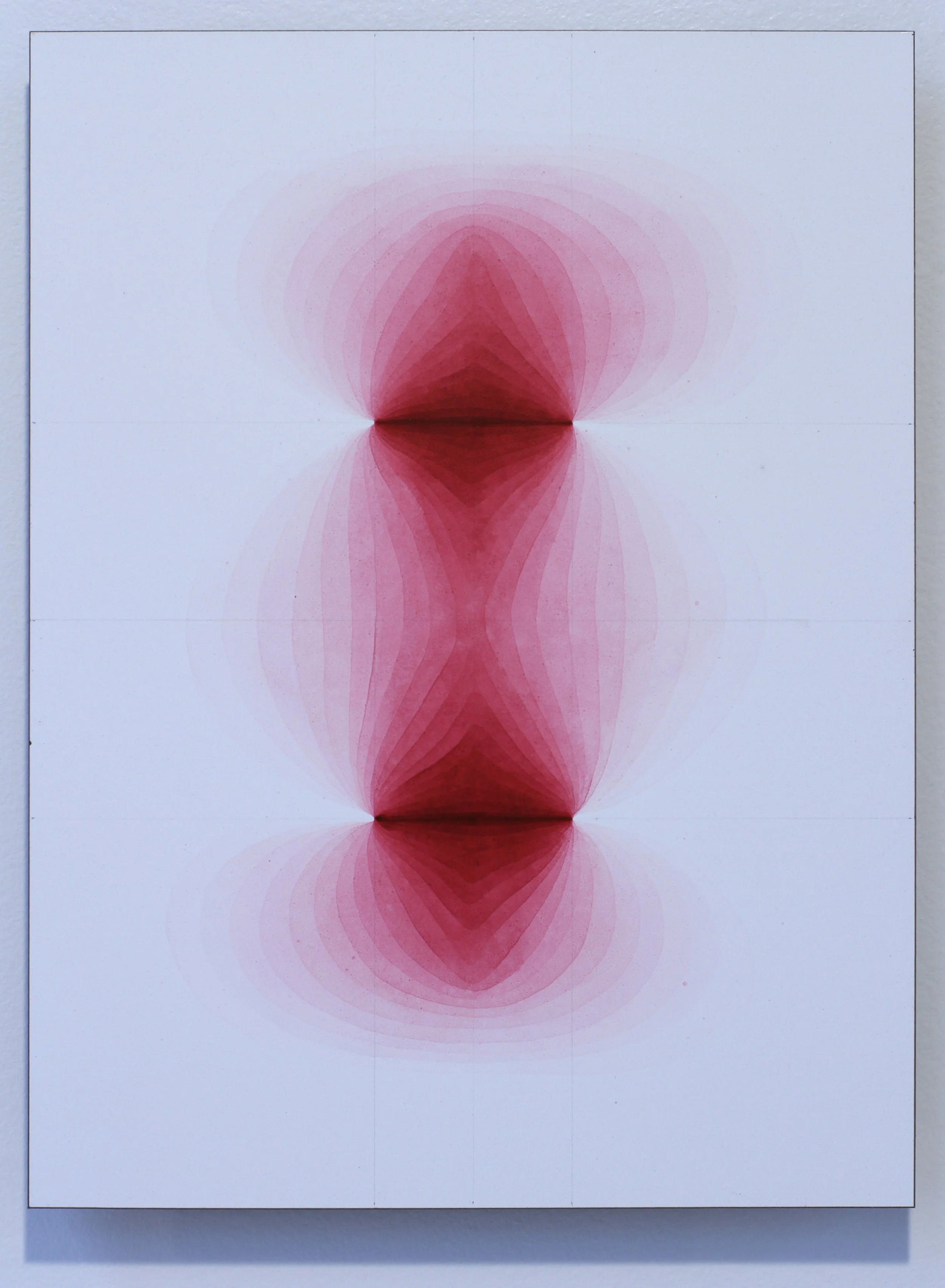

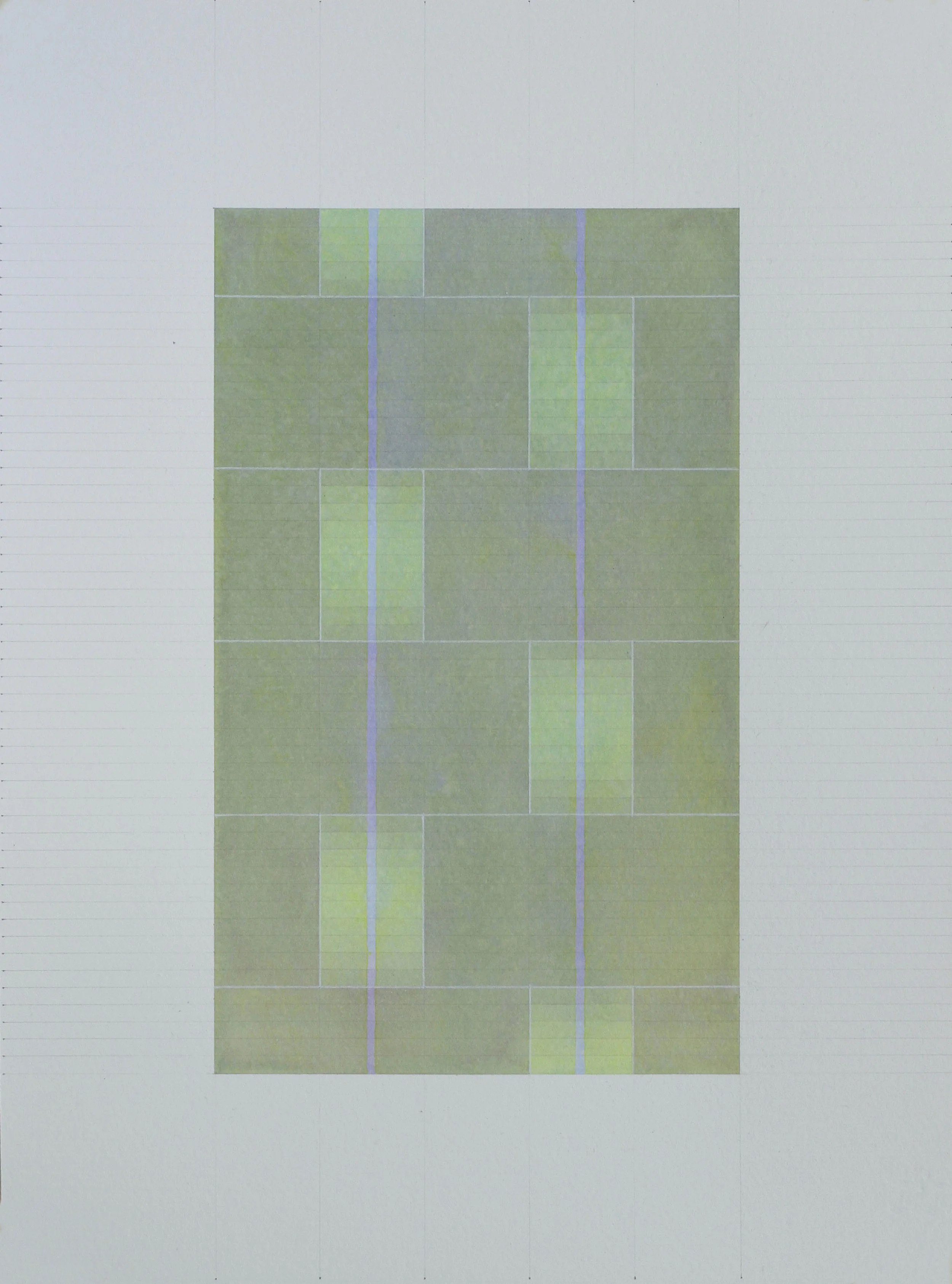

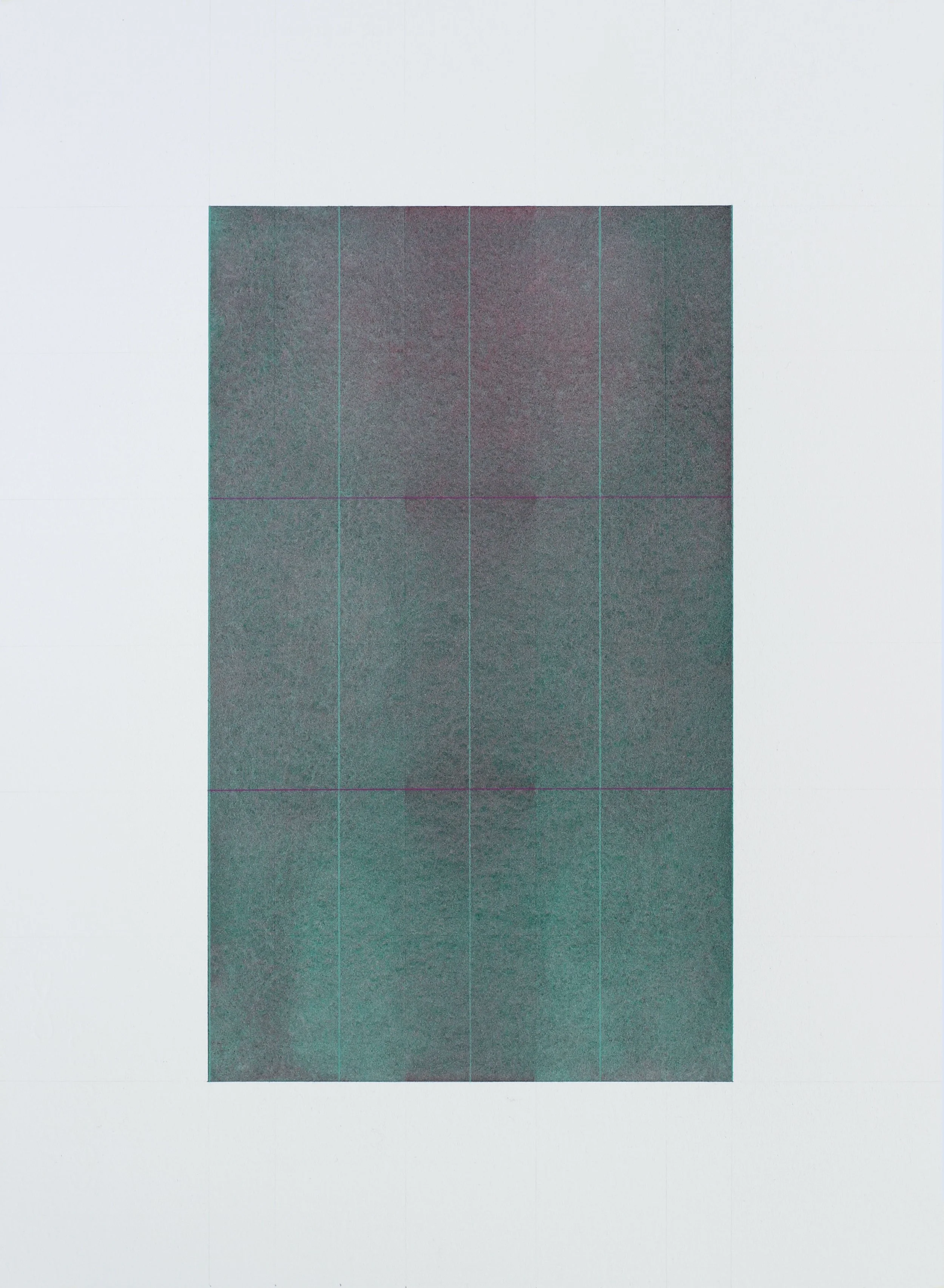

cotton (c), 9x12”, acrylic on panel

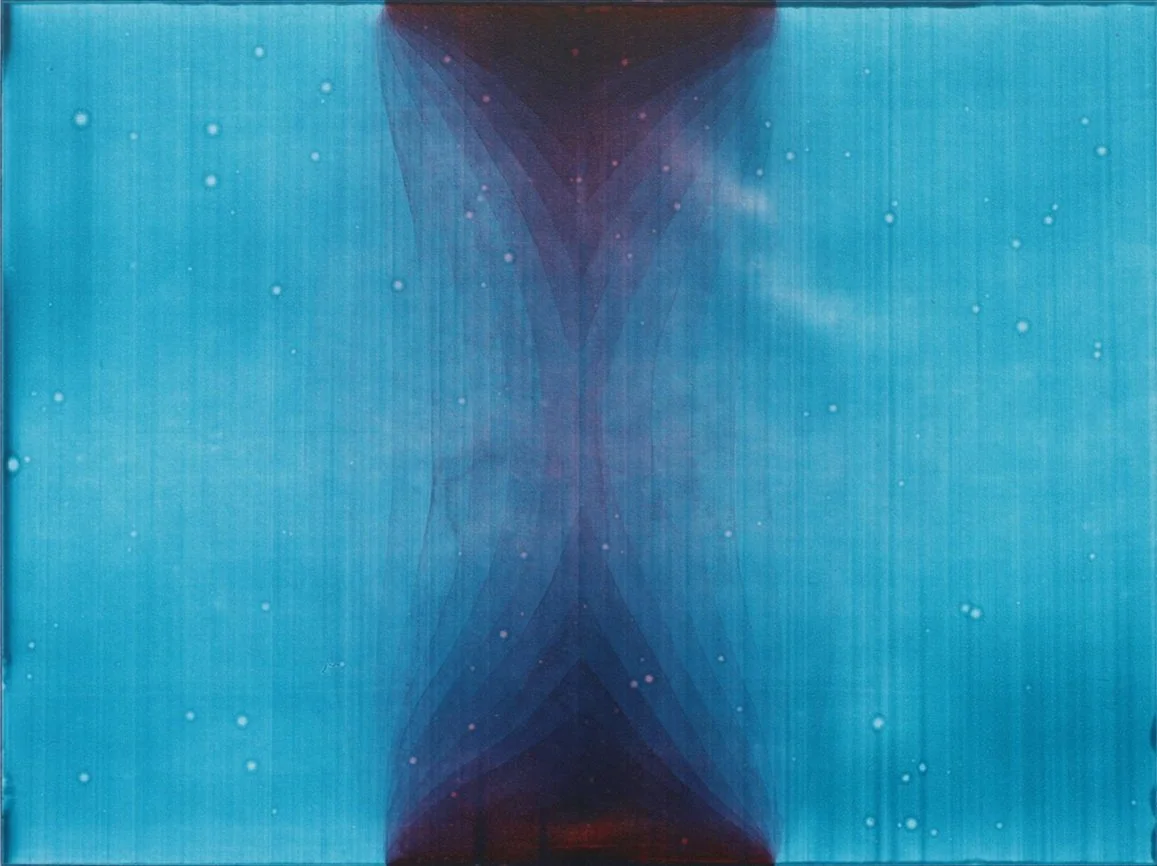

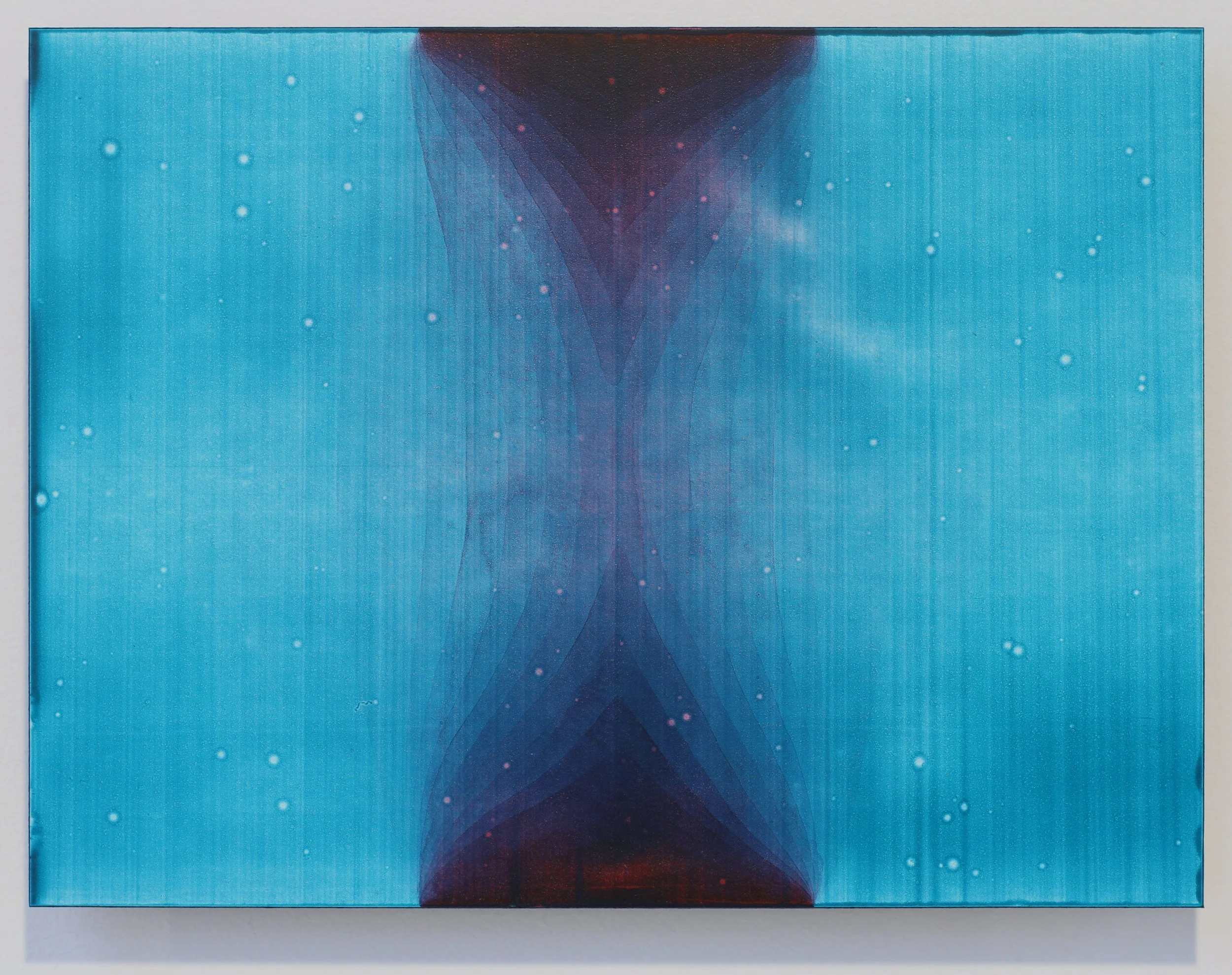

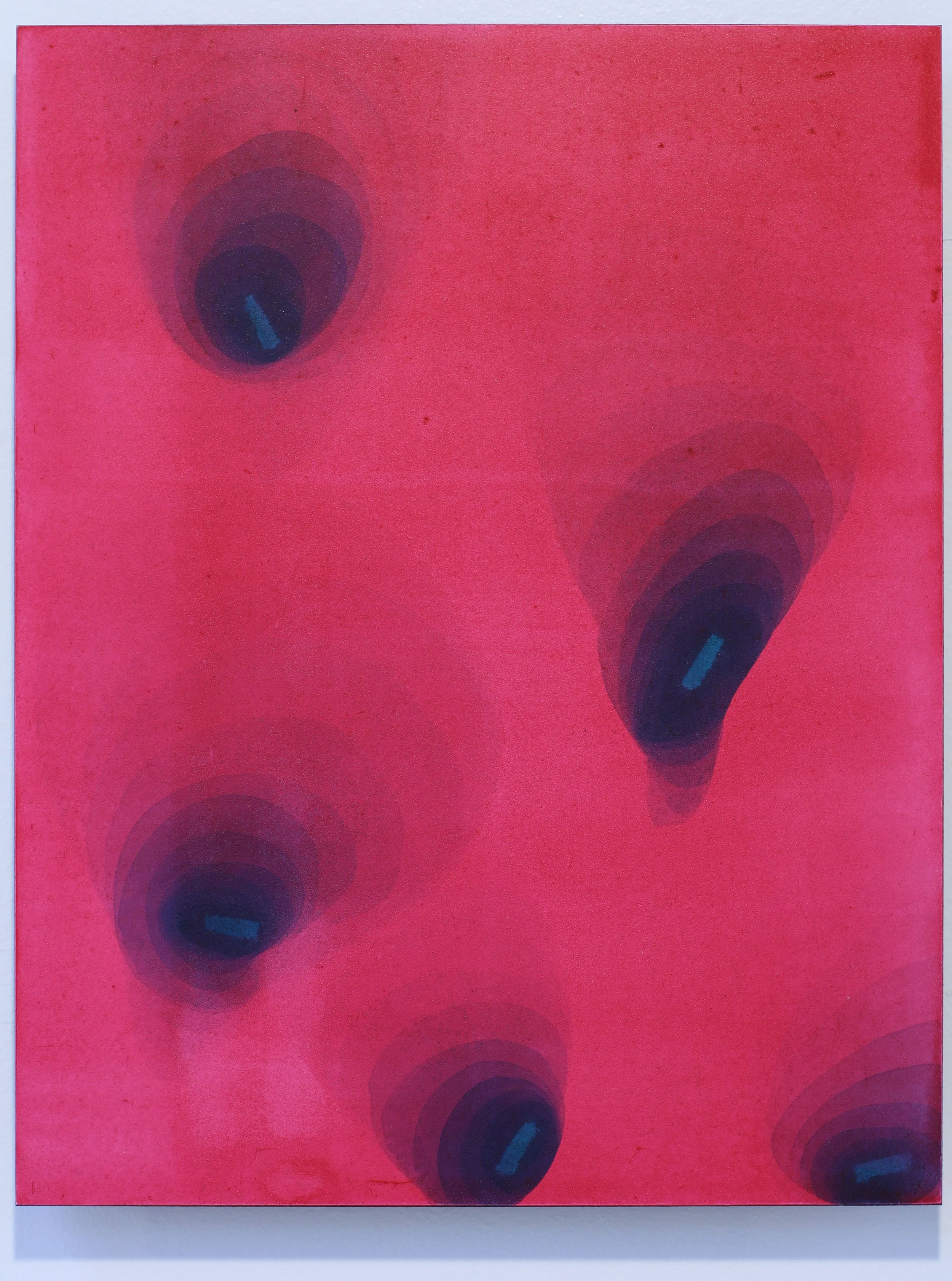

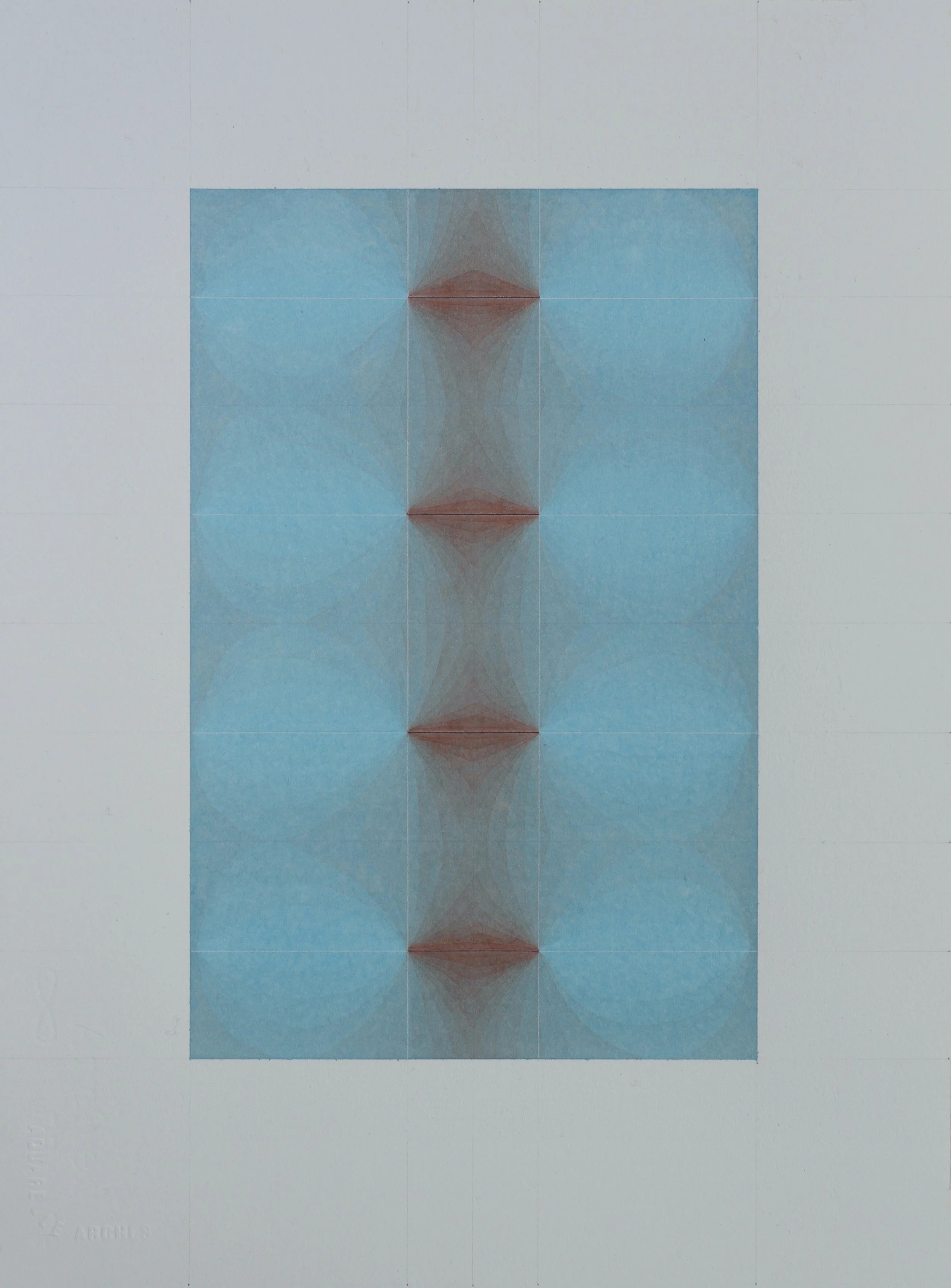

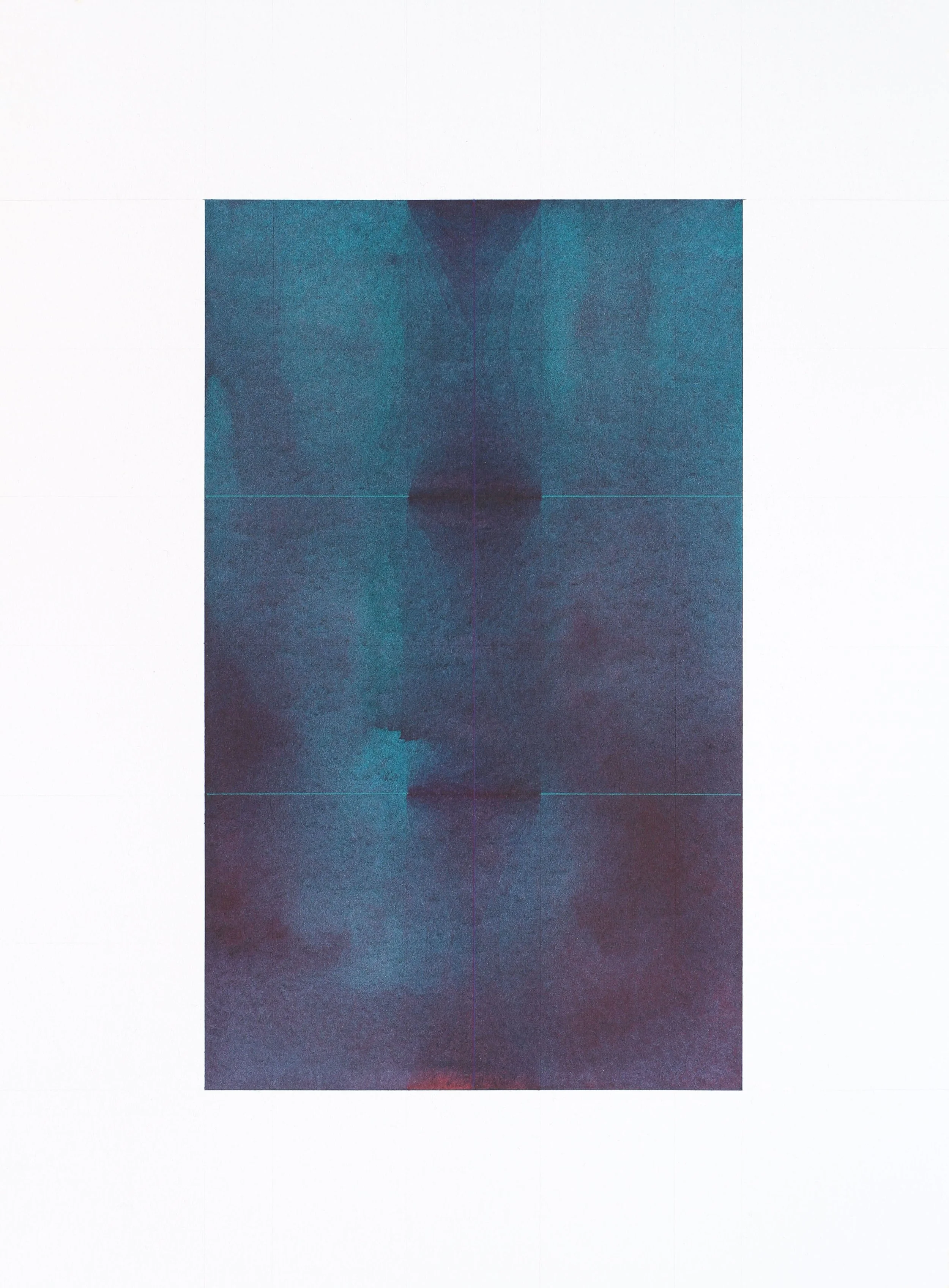

rain, ruin, 2021, 9x12”, acrylic on panel